Report outlining results of the Horizontal Evaluation of the Oceans Protection Plan at Transport Canada.

On this page

Acronyms and abbreviations

-

BMP

-

Building Meaningful Partnerships

-

CCG

-

Canadian Coast Guard

-

CEMS

-

Cumulative Effects of Marine Shipping

-

CRF

-

Coastal Restoration Fund

-

CSAP

-

Collaborative Situational Awareness Portal

-

DFO

-

Department of Fisheries and Oceans

-

ECCC

-

Environment and Climate Change Canada

-

EMSA

-

Enhanced Maritime Situational Awareness Platform

-

FY

-

Fiscal Year

-

HC

-

Health Canada

-

HE

-

Horizontal Evaluation

-

HEWG

-

Horizontal Evaluation Working Group

-

HR

-

Human Resources

-

ICBVP

-

Indigenous Community Boat Volunteer Program

-

IM/IT

-

Information Management/Information Technology

-

IRP

-

Indigenous Relations and Partnership

-

MTP

-

Marine Training Program

-

NIM

-

National Integration Model

-

NRCan

-

Natural Resources Canada

-

Oceans RFA

-

Reconciliation Framework Agreement for Bioregional Oceans Management and Protection

-

OPP

-

Oceans Protection Plan

-

OPPSES

-

OPP Stakeholder Engagement Solution

-

PDAs

-

Partner departments and agencies

-

POR

-

Public opinion research

-

PVM

-

Proactive Vessel Management

-

TC

-

Transport Canada

-

TMX

-

Trans-Mountain Expansion

-

WCTSS

-

World Class Tanker Safety System Initiative

Executive summary

This report presents the results of the horizontal evaluation undertaken in 2021-2022 of the first iteration of the Oceans Protection Plan (OPP). The first OPP initiative was a largescale, ambitious, and comprehensive program aimed at strengthening the safety, environmental protections, Indigenous partnerships, and scientific knowledge related to Canada’s marine sector. Its activities were jointly implemented by Transport Canada (TC), Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Canadian Coast Guard (DFO-CCG), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan). OPP funding totaled $1.5 billion over 5 years (fiscal year 2016/17 to fiscal year 2021/22), which, at the time, made it the largest investment ever made to protect Canada’s coasts and waterways.

The OPP horizontal evaluation was led by TC in collaboration with DFO-CCG, ECCC, and NRCan. The primary objective of the evaluation was to assess progress towards the achievement of intended outcomes across the four partner departments and agencies (PDAs) and all OPP activities from 2016 to 2021. Given that funding for many OPP activities has been renewed for an additional 5 to 9 years through Budget 2022, the evaluation placed special emphasis on identifying lessons and practices that could potentially inform the upcoming implementation of the renewed and enhanced OPP.

The evaluation assessed relevance, design, federal collaboration, implementation factors, progress and results, Indigenous inclusion, stakeholder engagement, and best practices/lessons learned. Data collection methods included key informant interviews, an internal survey, an environmental scan, a review of documents related to Indigenous inclusion, a results assessment, and financial analyses. From an analysis of these data, the following key evaluation findings emerged:

Finding 1: The OPP successfully met several key needs among PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders; the gaps that remain highlight the initiative’s ongoing relevance.

PDAs received funding through the OPP that supported their core mandates and bolstered marine and environmental programming, while many of its sub-initiatives opened avenues for Indigenous groups to participate more meaningfully in the marine sector and provided direct and indirect benefits to stakeholders. Gaps in meeting the needs of PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders arose mainly from A) the initiative’s primary focus on West Coast activities and priorities, B) the lack of advance inclusion of Indigenous groups in program design/planning, and C) the discovery of new needs and the creation of new expectations among Indigenous groups and stakeholders during the implementation of the OPP.

Finding 2: While the OPP’s design was innovative and comprehensive, it lacked an overarching narrative linking its diverse initiatives together in pursuit of longer-term strategic outcomes.

The OPP was highly ambitious, with 50+ sub-initiatives aimed at addressing diverse aspects of safety, environmental protection and restoration, science and technology, and Indigenous collaboration in the marine sector. Although this ambition was a strength in many ways, PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders often struggled to maintain a clear understanding of how individual activities connected to each other or to the OPP’s high-level goals. This lack of a common unifying narrative hindered coordination and contributed to siloed approaches within and between PDAs.

Finding 3: The OPP’s strong focus on West Coast concerns and priorities was at odds with its comprehensive branding, contributing to dissatisfaction among some Indigenous groups and stakeholders.

Many OPP sub-initiatives were designed to address priorities and concerns related to increased shipping and the transportation of oil on the West Coast, resulting in a higher concentration of activities and investments in the Pacific compared to other regions. While this was an intentional design choice, the discrepancy created dissonance with the OPP’s branding as a Canada-wide, comprehensive marine protection initiative, contributing to a sense of dissatisfaction among Indigenous groups and stakeholders in other regions as well as those with differing safety and environmental priorities.

Finding 4: Internal services and Indigenous groups had limited opportunities to provide input into program planning and development, leading to underestimations of the time and resources required for some activities.

Time constraints during the OPP’s planning phase meant that many of its sub-initiatives were developed quickly and in a centralized manner, with limited consultation opportunities for internal services or Indigenous groups. Because of the time pressures and the complexity of the OPP, the time and resources needed by enabling functions such as Human Resources (HR) and Information Management/Information Technology (IM/IT) to support OPP activities were underestimated. Similarly, the lack of advance engagement with Indigenous groups led to underestimations of the investments required for meaningful Indigenous inclusion. These factors contributed to a slow start for some projects and hindered relationship-building efforts during the OPP’s early implementation.

Finding 5: Strong federal collaboration was critical to the implementation of many OPP activities. While collaboration within PDAs was generally effective, horizontal dynamics were more challenging.

A defining feature of the OPP was its dependence on effective horizontal relationships to achieve intended outcomes. PDAs’ differing mandates, cultures, and communication styles sometimes impeded efforts to collaborate. However, there are early indications that this situation may be improving as the initiatives mature and experience accrues within the federal public service.

Finding 6: There were issues coordinating and tracking engagement and partnership activities in a consistent and reliable manner, which placed strain on Indigenous groups and stakeholders. Many improvements to the engagement process occurred as the OPP matured, but opportunities for improvement remain.

The magnitude of engagement sessions conducted through the OPP (and other related federal initiatives) placed high demands on many partners, especially Indigenous groups. Some partners found the experience of engaging with multiple OPP sub-initiatives to be confusing or uncoordinated, straining their ability to participate. Although PDAs have recognized this problem and begun working to streamline the engagement process, opportunities for improvement remain.

Finding 7: OPP staff were agile and effective in responding to significant changes over the course of the OPP implementation, reflecting the program’s spirit of flexibility and experimentation.

The OPP was a space that encouraged transformation and flexibility, giving staff the ability to pilot new approaches, respond to feedback from partners, and adapt to challenging and evolving circumstances (such as the COVID-19 pandemic). This working-level agility was recognized as a strong success factor for the initiative’s implementation by internal and external interviewees.

Finding 8: Despite the challenges associated with the early implementation and delays caused by the pandemic, the OPP had significant positive impacts and made tangible progress in key thematic areas.

Many OPP sub-initiatives experienced delays due to: A) the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on engagement activities, field work, and legislative processes, B) the initial miscalculations of key enabling requirements (e.g., the time it would take to hire and train staff, limited capacity for data storage/management), and C) the underestimations of the time and resources required to support meaningful Indigenous inclusion. Despite these challenges, PDAs made significant progress through key activities that strengthened marine safety, ecosystems protection and restoration, Indigenous inclusion, and scientific knowledge.

Finding 9: The OPP started an important foundation for longer-term work by building relationships, identifying gaps, developing skills, and strengthening scientific knowledge related to the marine sector.

The OPP can be seen as an effective first step in the ongoing process of modernizing and strengthening Canada’s marine system and has laid the groundwork for future activities in this area by: A) developing relationships and working to establish trust with Indigenous groups and stakeholders, B) identifying gaps and reinvesting in core priorities, C) building up the requisite knowledge, skills, and experience within the federal public service, and D) collecting critical data to inform marine decision-making.

Finding 10: While performance information was helpful for project management and decision making, reporting requirements placed a significant burden on working-level OPP staff and did not always provide a meaningful assessment of strategic progress.

The quantity and detail of performance information collected under the OPP allowed senior staff to effectively monitor progress and make informed decisions. However, heavy oversight and reporting requirements (especially in the early days of the OPP’s implementation) were sometimes seen as pulling resources away from project delivery. In addition, performance metrics did not always align well with activities at the working level.

Finding 11: Although Indigenous engagement was a key priority for many OPP initiatives, Indigenous groups were often seeking a deeper level of collaboration than PDAs were prepared to accommodate.

Many OPP activities were well matched to the goals and priorities of Indigenous communities and organizations. However, efforts on the part of PDAs to shift towards new ways of collaborating with these groups in the marine sector have been inconsistent and challenging. Limited resources, capacity constraints, administrative barriers, and concerns surrounding the inclusion of external groups in insular departmental design and decision-making processes have prevented the OPP from fully meeting Indigenous needs, leading to tension and frustration in some cases. Going forward, Indigenous groups have expressed a clear expectation to be treated as full partners (not just a special category of stakeholders) in developing and delivering marine programming that impacts their rights and territories.

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are made:

- Indigenous capacity and meaningful collaboration

- Recommendation: It is recommended that TC, in collaboration with OPP PDAs, develop and implement a strategy/approach to enhance the coordination and tracking of engagement sessions with Indigenous groups and stakeholders.

- Rationale: A coordinated and consistent approach to engage with Indigenous groups and stakeholders will be important for the renewed OPP to ensure the effectiveness of the engagement efforts and to alleviate capacity strain. Existing tools like the National Integration Model (NIM) and the OPP Stakeholder Engagement Solution (OPPSES) have been effective and there is potential to utilize and enhance the uptake of these tools, as a component of such an approach.

- Results chain/narrative

- Recommendation: It is recommended that TC, in collaboration with OPP PDAs, ensure that a comprehensive results chain and narrative (which includes outcomes, performance indicators, targets, and a data strategy) for the renewed OPP is available and disseminated once the initiative is launched.

- Rationale: Having this tool will provide a variety of benefits. Internally, a logical and well-defined results chain with an accompanying narrative should allow OPP staff to easily comprehend the interconnections between activities and how they contribute to the achievement of long-term results. Further, a well-developed results chain/narrative should help to rationalize reporting requirements, enhance staff engagement, allow the program to gauge the OPP’s performance continuously, enhance agile decision making, and facilitate external communications related to the achievement of results to partners, central agencies, and the Canadian public.

- Horizontal collaboration/communication

- Recommendation: It is recommended that TC, in collaboration with OPP PDAs, develop and/or enhance tools to facilitate collaboration and communication between and within departments to ensure that OPP staff are kept abreast of changes to the OPP organizational structure, changes in personnel, and key decisions taken by senior managers that could impact their work.

- Rationale: These tools would facilitate effective collaboration among internal partners, and could include, but are not limited to, developing and routinely updating a contact list for all OPP sub-initiatives, expanding upon the routine communications sent by departmental Communications teams (e.g., the “OPP Comms Calendar of the Week”), or having OPP secretariats launch a centralized and integrated forum with representatives from all PDAs and from all departmental regions.

1.0 Program profile

In 2016, the Prime Minister announced $1.5 billion to fund the Oceans Protection Plan (OPP) over 5 years (2016/17 to 2021/22), which at the time was the largest investment the Government of Canada had ever made to protect its coasts and waterways. The OPP was envisioned as a comprehensive, transformative strategy to build a world-leading marine safety system and protect Canada’s marine ecosystems. This strategic outcome is supported by four main pillars, each with its own set of shared outcomes and associated initiatives:

- State of the Art Marine Safety System (14 initiatives)

- Preservation and Restoration of Marine Ecosystems (4 initiatives)

- Indigenous Partnerships (2 initiatives)

- Stronger Evidence Base, and Increased Community Participation and Public Awareness (3 initiatives)

Given the broad scope of activities associated with some of these initiatives, many were further broken down into separate (but interrelated) sub-initiatives; for example, the Comprehensive Strategy for Vessels of Concern initiative consisted of 6 sub-initiatives addressing various aspects of owner identification and remediation, risk-based strategizing, vessel removal, education and outreach, and research into recycling and design. Management and reporting for the OPP was generally done at the sub-initiative level.

In total, the first iteration of the OPP consisted of 57 sub-initiatives which were implemented by the four OPP partner departments/agencies (PDAs): Transport Canada (TC), Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Canadian Coast Guard (DFO-CCG), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan); see Table 1. Full details of the OPP’s initiatives and sub-initiatives including intended outcomes, performance indicators, and funding amounts can be found in Appendix A.

| PDA | Sub-initiatives led | Sub-initiatives contributed to |

|---|---|---|

| TC | 26 | 6 |

| DFO | 10 | 3 |

| CCG | 19 | 9 |

| ECCC | 2 | 3 |

| NRCan | - | 1 |

1.1 Geographic and political context

The OPP operates within the context of other high-profile federal government priorities and initiatives, including the Reconciliation Agenda and the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) project. In the years leading up to its development, high-profile marine incidents (such as the near grounding of a Russian cargo vessel off the coast of Haida Gwaii in 2014Footnote 1 and the Marathassa oil spill in English Bay in 2015Footnote 2) combined with the anticipation of increased shipping activity from TMX and other energy infrastructure projects contributed to an environment of heightened concern around the safety and sustainability of marine activities on the West Coast, particularly within Indigenous groups and coastal communities. Previous investments in marine safety and spill preparedness made through the World Class Tanker Safety System Initiative (WCTSS; 2013-2016), while significant, were insufficient to fully address public, provincial, and Indigenous concerns in this area. Given this context, the OPP was designed to build upon work completed under the WCTSS to:

- Help restore public confidence in Canada’s marine safety system to protect coastal ecosystems from the impacts of increased shipping,

- Address potential impacts to Indigenous rights and interests for the TMX project through the implementation of marine-based accommodation measures related to environmental protection and marine safety,Footnote 3 and

- Respond to several other broad federal objectives and 2016 mandate letter commitments, including pursuing reconciliation with Indigenous groups, delivering the moratorium on Crude Oil Tanker Traffic on BC's North Coast, re-establishing the Maritime Rescue Sub-Centre in St. John's, Newfoundland, and achieving benefits for groups that were traditionally underrepresented in the marine sector.

The OPP provided funding for a diverse set of activities related to marine health and safety, ranging from increasing access to real-time marine traffic and weather data, conducting research into oil spill clean-up technologies, restoring coastal ecosystems, and creating a greater role for Indigenous groups in the marine safety regime. While many aspects of this work were already underway within individual departments, the OPP’s comprehensive branding cut across multiple mandates and prompted new levels of horizontal coordination. At the same time, the initiative’s ties to TMX and the Reconciliation Agenda demanded a much stronger focus on engagement and partnerships with Indigenous groups.

2.0 Evaluation background

The Horizontal Evaluation of the OPP (OPP HE) was led by TC in partnership with DFO-CCG, ECCC, and NRCan. Working-level collaboration with evaluation partners was coordinated through a Horizontal Evaluation Working Group (HEWG) whose members provided input and expertise and facilitated access to key contacts and information from within their departments. The formal planning for the OPP HE was launched in May 2021, with the final Evaluation Plan approved by Heads of Evaluation in all four PDAs in October 2021. The evaluation was conducted between December 2021 and March 2022.

A key contextual factor to consider for this evaluation is that the conduct phase occurred in parallel with the development and approval of OPP renewal documents (as well as Budget 2022). As such, at the time of writing, work may already be underway to address certain issues flagged in this report. Where possible, findings and recommendations that are particularly relevant to the upcoming implementation of the renewed OPP are emphasized. Other findings have been included for their potential value in informing similar large federal initiatives in the future.

2.1 Objective and scope

The aim of this evaluation was to critically examine progress towards OPP outcomes across all 57 sub-initiatives. The scope of the evaluation covered the period from the OPP’s early implementation in April 2017 to March 2021; however, in some cases, more recent data (up to March 2022) was also considered. The following evaluation questions were examined:

- Relevance: To what extent is the OPP meeting the needs of PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders?

- Design: To what extent was the OPP designed in a way that would facilitate the achievement of its intended outcomes?

- Federal Collaboration: To what extent has collaboration within and between OPP PDAs been successful in terms of achieving results?

- Process/Implementation: To what extent was the OPP implemented in a way that would facilitate the achievement of its intended outcomes?

- Progress & Results: To what extent has the OPP made progress towards its intended strategic outcome and shared outcomes?

- Indigenous Inclusion: How were Indigenous communities and organizations included within the OPP?

- Stakeholder Engagement: How did PDAs engage and partner with stakeholder groups?

- Lessons Learned: What best practices and lessons learned does the OPP offer for future planning of similar federal horizontal initiatives?

The full evaluation matrix including sub-questions and indicators can be found in Appendix B.

2.2 Methodology and limitations

Data collection for this evaluation consisted of:

- key informant interviews,

- an internal survey of OPP staff,

- an environmental scan and general document review,

- a targeted review of materials related to Indigenous inclusion,

- an assessment of progress towards the OPP’s intended results, and

- financial analysis.

Methods and limitations for each of these lines of evidence are described below.

Key informant (KI) interviews

Sixty-eight individual and small group interviews were conducted between December 2021 and March 2022, including 44 with internal informants (see Figure 1) and 24 with external informants (see Figure 2). In total, 104 interviewees were consulted through this process.

Figure 1. Internal interviews by PDA

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of interviews with internal informants by OPP partner department/agency. Fifty-five percent of interviews were conducted with TC informants, 36% with DFO-CCG informants, 7% with ECCC informants, and 2% with NRCan informants.

Figure 2. External interviews by region

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of interviews with external informants by region. Thirty percent of interviews were conducted with Atlantic informants, 26% with Pacific informants, 18% with Quebec informants, 13% with Arctic informants, and 13% with Ontario informants.

The number and diversity of OPP activities presented challenges for the evaluation, as it was not possible to interview all potential informants. To ensure adequate coverage of perspectives, internal interviewees were selected via a combination of purposive and stratified random sampling, with HEWG members providing corrections and additions as necessary. External interviewees were identified by requesting suggestions of key stakeholders from regional engagement staff and consisted of key contacts from industry groups and private companies (33% of interviews), environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs; 21%), marine authorities (e.g., port and pilotage authorities; 21%), other levels of government (13%), research and academic institutions (8%), and external subject matter experts (4%).

All interview notes were coded using the qualitative analysis software NVivo.Footnote 4 Likert-type rating scales were used in addition to open-ended questions to initiate discussion during interviews. See Appendix C for a full list of internal and external interview questions.

Quotes from internal and external interviews are presented throughout the text of this report without attribution. In some cases, the original wording has been changed slightly to increase clarity or preserve the confidentiality of interviewees.

On the advice of program staff, a decision was made not to reach out directly to Indigenous groups for interviews during the evaluation’s conduct phase given:

- The issue of widespread capacity strain within many Indigenous communities, including competing demands from other federal programs and engagement activities;

- The wealth of pre-existing materials capturing Indigenous perspectives on the OPP; and

- The potential redundancy with other engagement activities, including forward planning processes for OPP renewal (which had recently sought feedback from partners on similar issues).

Instead, views of Indigenous groups were assessed using secondary data (see Review of documents related to Indigenous inclusion below). While this review supplemented PDA-authored sources with publications from Indigenous organizations, documented input from partners in their own words, and results of third-party research with Indigenous respondents, this absence of direct engagement is still an important limitation for the evaluation and should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings and recommendations contained in this report.

Internal survey

A confidential online survey was sent to OPP staff in all four PDAs through the secure web-based platform SimpleSurvey.Footnote 5 A total of 346 participants were invited via email to complete the survey online between February 24 and March 31, 2022. A response rate of 30% resulted in 105 completed responses which were then downloaded, cleaned, and analyzed in Microsoft Excel. Figure 3 presents the departmental breakdown of survey respondents. Survey questions (see Appendix D) closely matched the questions posed to internal interviewees, including rating scales and options to enter long-form responses. Additionally, respondents were asked to rate the degree of challenge created by various implementation factors.

Figure 3. Survey respondents by PDA

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of internal survey respondents by OPP partner department/agency. Forty-seven percent of respondents were from DFO-CCG, 46% were from TC, 6% were from ECCC, and 1% were from NRCan.

Internal survey data is represented through graphs and percentages (rounded to the nearest whole number) throughout this report. Given its more limited role in the OPP, there were not enough NRCan respondents to allow for meaningful comparison with other PDAs; for this reason (and to preserve respondents’ confidentiality), NRCan data is not included in subsequent graphics that compare survey results between PDAs.

While survey results provided a useful snapshot of the relevance, design, expected results, and collaboration from the perspective of OPP staff, there were several issues that likely affected the response rate. These included a technical error with the survey link (which was resolved after respondents brought it to the evaluation team’s attention), the timing of the survey overlapping with March break in some provinces, and departments’ availability during the end of the fiscal year and the drafting of OPP program renewal documents. The survey deadline was extended beyond the originally planned closing date to mitigate these issues.

Review of documents related to Indigenous inclusion

Materials related to Indigenous inclusion were identified through targeted requests made to engagement and program staff within TC (50 documents) and DFO-CCG (146 documents); while ECCC and NRCan were referenced in many of these materials, separate document requests were not made through these departments given their lower involvement with OPP engagement activities. Submissions included internal reports, project charters, summaries of best practices and lessons learned, engagement statistics, public opinion research (POR), media items, records of discussion from various engagement activities, and external publications. Supplemental information and materials identified by the evaluation team through internal queries and internet searches were also included where relevant. From an initial scan of these materials, key documents were identified for in-depth review. Others were imported into NVivo and scanned for relevant content using the software’s query function.

It should be noted that Inuit, First Nations, and Métis groups with interests in the marine sector have varied perspectives and priorities based on history, culture, geography, internal capacity, Aboriginal or Treaty rights, and other factors. While the evaluation team tried to extract common themes where appropriate, the findings in this report do not represent the full range of Indigenous views on the OPP. In particular, the perspectives of groups who were either unable or unwilling to engage with PDAs are not included here.

Environmental scan and general document review

Over the course of the OPP’s 5-year delivery, a variety of related horizontal evaluations, departmental evaluations, audits, and research activities were conducted to address specific information needs among PDAs. Key examples included:

- OPP Case Studies: Lessons Learned (TC-led, 2021);

- Evaluation of the Environment and Climate Change Canada components of the OPP (ECCC, 2021);

- Evaluation of the OPP (Phase 1) (DFO-CCG, 2019).

Along with related federal initiatives and core program documentation, these reports provided a wealth of useful information to support the OPP HE. The evaluation team conducted a review of approximately 34 documents, which were analyzed in relation to the assessment criteria and evaluation questions.

Results assessment

The evaluation team analyzed content from OPP placemats, sub-initiative results templates, project charters, public reports, POR, and audits to assess progress towards intended results, with a particular focus on:

- the six performance indicators developed to track progress on the OPP’s strategic outcome (A world-leading marine safety system for Canada’s three coasts that protects marine ecosystems; see below),

- high level summaries of tangible OPP outputs, and

- sub-initiatives’ reported results.

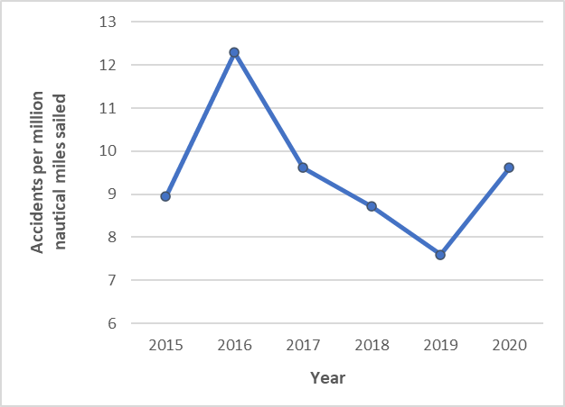

OPP Strategic Outcome Performance Indicators:

- Number of marine safety incidents and spills from vessels in Canada’s waters

- Percentage of projects funded through Coastal Restoration Fund contribution agreements leading to rehabilitation of aquatic habitats

- Number of vessels of concern addressed

- Number of Indigenous groups that participate in Canada’s marine safety system

- Percentage of policies and operational response plans developed through OPP that are supported by scientific, local/traditional, and other relevant information/knowledge

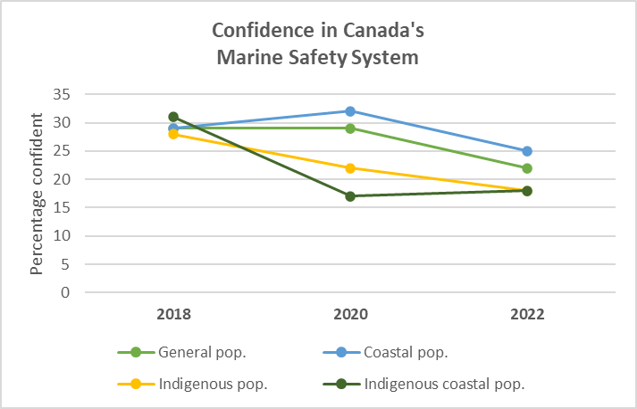

- Percentage of Canadians who are confident in Canada’s marine safety system

While the reviewed documentation provided reasonably strong reporting of outputs at the sub-initiative level, the results reporting for the OPP’s short-term outcomes (i.e., sub-initiatives’ shared outcomes), medium-term outcomes, and long-term outcome, was not as strong, which constrained the evaluation team’s ability to meaningfully assess overall progress towards strategic results.

Financial analysis

To facilitate the financial analysis, PDAs provided the evaluation team with internal financial documentation and contextual information for how resources were used during the implementation of the OPP. Additional summary financial tables for the years 2018-19, 2019-20, and 2020-21 were extracted from Departmental Results Reports published on TC’s website along with general information on the horizontal initiative. These tables included allocated funding, planned and actual spending, and actual results for the corresponding fiscal year, broken down by OPP pillar and PDA. These data were cleaned, aggregated, and analyzed in Microsoft Excel. While this analysis allowed the evaluation team to identify macro-level trends and outliers, the available data did not contain details of concrete results or purchases made at the sub-initiative level, making it difficult to connect the financial analysis to other lines of evidence.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Relevance

Finding 1: The OPP successfully met several key needs among PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders; the gaps that remain highlight the initiative’s ongoing relevance.

The OPP was designed to address a wide range of marine safety and environmental issues across a variety of groups. For the purposes of the OPP HE, these groups were categorized as follows:

- PDAs: federal partner departments and agencies (TC, DFO-CCG, ECCC, and NRCan)

- Indigenous groups: individual communities and aggregate organizations

- Stakeholders: the Canadian public, industry (private companies and advocacy groups), NGOs, other levels of government, etc.

For a more detailed description of these categories, see Appendix E.

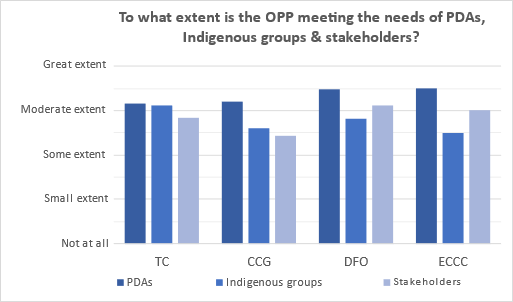

As seen in Figure 4, OPP staff generally viewed the OPP as being most effective in meeting the needs of PDAs. Overall, while 68% of all survey respondents indicated that the OPP was meeting PDA needs to a moderate or great extent, this rating fell to 56% for Indigenous groups and 51% for stakeholders. Perceptions of the OPP’s relevance to different groups varied by PDA, with higher ratings of PDA relevance among respondents from DFO and ECCC compared to CCG or TC. TC respondents held the most positive views of the extent to which the OPP had met the needs of Indigenous groups.

Figure 4. Average relevance ratings by PDA (internal survey data)

Note: NRCan data too limited for meaningful comparison

Text version

This bar chart shows average ratings given by internal survey respondents in each OPP partner department/agency (excluding NRCan) in response to the question "To what extent is the OPP meeting the needs of PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders"? Ratings are presented for three separate categories: PDAs, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders. On a scale from 0 ("Not at all") to 4 ("Great extent"), TC respondents gave an average rating of 3.15 for PDAs, 3.13 for Indigenous groups, and 2.84 for Stakeholders. CCG respondents gave an average rating of 3.2 for PDAs, 2.61 for Indigenous groups, and 2.44 for stakeholders. DFO respondents gave an average rating of 3.48 for PDAs, 2.82 for Indigenous groups, and 3.11 for Stakeholders. ECCC respondents gave an average rating of 3.5 for PDAs, 2.5 for Indigenous groups, and 3 for Stakeholders.

PDAs received significant funding through the OPP that bolstered marine and environmental programming, addressed specific departmental needs, and supported their core mandates. Some examples highlighted through internal informant interviews included:

- funding for TC to increase Canada’s marine influence on the international stage,

- large investments in modernizing emergency response infrastructure and replacing ageing fleet assets within CCG,

- dedicated resources for ECCC to strengthen the evidence base in support of environmental planning and response on the West coast, and

- responding to concerns expressed by the public and Indigenous groups about West Coast energy development.

“We’ve moved lightyears ahead, and it’s really related to the foundation of that investment from OPP.”

In fact, a portion of OPP funding was earmarked to support internal PDA processes and address shortfalls resulting from past budget cuts. One interviewee noted that this reality caused confusion among some Indigenous groups and stakeholders, whose expectations were high following the government’s announcement of 1.5 billion in funding for the initiative.

Activities that were the most effective in meeting the needs of Indigenous groups included those that:

- directly strengthened community-level search and rescue and/or environmental response capacity (e.g., the Indigenous Community Boat Volunteer Program (ICBVP)),

- empowered communities to be directly involved in program development and decision-making (e.g., the Enhanced Maritime Situational Awareness (EMSA) platform), or

- provided opportunities for environmental stewardship through the integration of traditional and local knowledge (e.g., the Cumulative Effects of Marine Shipping (CEMS) sub-initiative).

Despite these positive examples, most internal interviewees felt that Indigenous perspectives on the OPP’s relevance were variable and that much of the work of increasing their participation in the marine sector still lay ahead. Indigenous groups were often looking to be involved earlier in the process of setting marine priorities and designing programs, as full partners and decision-makers rather than just stakeholders; with some exceptions, the OPP fell short of meeting this expectation. Some of the factors that impeded progress with Indigenous groups were partially or completely external to PDAs, including pre-existing capacity challenges within Indigenous groups and the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited in-person engagement. Other challenges reflected planning missteps or misalignment between Indigenous priorities and the PDA norms and processes. For example, the current realities of policy development require confidentiality until proposals are approved by Cabinet. Key gaps and barriers to meeting Indigenous needs are examined in detail in the Design and Indigenous Inclusion sections of this report.

Internal and external interviewees largely agreed that the OPP did not prioritize stakeholders to the same degree as Indigenous groups, leading some stakeholder groups (such as industry) to feel left out from key conversations and processes. However, most interviewees recognized that this disparity was largely by design; in accordance with the OPP’s strong focus on reconciliation, PDAs made strategic decisions to direct limited resources towards engagement with Indigenous groups. While their needs were often secondary, many OPP projects still provided direct or indirect benefits to NGOs, industry, federal authorities, and other groups by creating new funding opportunities and opening up new spaces for dialogue between marine stakeholders. The impacts of the OPP on stakeholders are discussed in the Stakeholder Engagement section of this report.

“There is a stakeholder desire for more, deeper analysis, deeper participation. It’s like Pandora’s box – once you open it, there’s more to do.”

While some very specific needs (such as gaps in Arctic charting data and the need for ongoing maintenance investments for new infrastructure and equipment) were flagged as still outstanding by interview and survey respondents, the most significant gap was the OPP’s strong geographical focus on the West Coast, with more limited resources directed towards activities in other regions. While many OPP projects were geared specifically towards addressing West Coast concerns and priorities, the high price tag for the initiative and its comprehensive branding as a Canada-wide “Oceans Protection Plan” created strong levels of interest across the country. Combined with high-level comments framing the OPP as a path to reconciliation, the resulting appetite for participation among Indigenous communities and other groups sometimes exceeded what PDAs were prepared to accommodate, both in terms of resource availability and limitations imposed by institutional norms and processes. The implementation of the OPP also led to the discovery of new needs and raised expectations among Indigenous groups and stakeholders, setting a new standard for the level and quality of engagement on marine issues. There have been consistent calls for initiatives to be continued and expanded, highlighting the ongoing relevance of OPP activities and the work still to come following OPP renewal.

3.2 Design

Finding 2: While the OPP’s design was innovative and comprehensive, it lacked an overarching narrative linking its diverse initiatives together in pursuit of longer-term strategic outcomes.

The OPP was designed as a comprehensive, transformative, and very ambitious strategy to modernize and strengthen Canada’s marine system, providing space to experiment with new approaches to safety, environmental protection, and increasing the participation of marginalized groups. This led to both opportunities and challenges for PDAs.

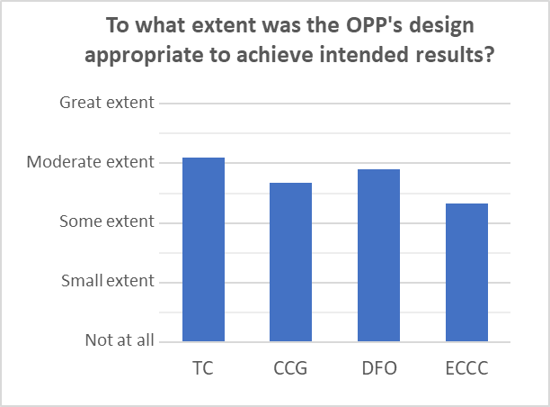

Figure 5. Average design ratings by PDA (internal survey data)

Note: NRCan data too limited for meaningful comparison

Text version

This bar chart shows average ratings given by internal survey respondents in each OPP partner department/agency (excluding NRCan) in response to the question "To what extent was the OPP's design appropriate to achieve intended results?" On a scale from 0 ("Not at all") to 4 ("Great extent"), TC respondents gave an average rating of 3.09; CCG respondents gave an average rating of 2.68; DFO respondents gave an average rating of 2.89; and ECCC respondents gave an average rating of 2.33.

As seen in Figure 5, perspectives on the OPP’s design were mixed. Many internal and external interviewees praised the OPP’s range and ambition in giving PDAs the resources, mandate, and flexibility to address many long-standing issues and pilot new technologies and processes (such as co-development of marine activities with Indigenous communities). On the other hand, some felt that efforts to make the OPP as broad and inclusive as possible resulted in a lack of cohesion between its many diverse activities and sub-initiatives, which were individually valuable, but difficult to link to a single broad policy objective. Connections between some activities were especially abstract/high-level (e.g., between search and rescue activities and environmental restoration projects), making it difficult for PDAs to recognize links and report on shared, bigger-picture outcomes in a collaborative manner. To this point, multiple interviewees suggested that both internal and external groups often struggled to fully grasp how OPP activities connected to each other and to the initiative’s strategic outcomes.

This lack of common understanding ultimately hindered coordination, contributing to siloed approaches within and between PDAs, and added confusion and strain to some Indigenous groups and stakeholders. Many internal interviewees suggested that a clear, intuitive narrative explaining the links in the OPP’s results chain would have helped to emphasize shared goals and progress, while also facilitating the task of communicating the value of the OPP to central agencies, external partners, and the Canadian public.

Finding 3: The OPP’s strong focus on West Coast concerns and priorities was at odds with its comprehensive branding, contributing to dissatisfaction among some Indigenous groups and stakeholders.

Given the strategic decision to use the OPP as a vehicle to address TMX-related concerns, its design closely reflected West Coast priorities and political considerations. Several OPP activities (such as the EMSA and CEMS sub-initiatives) are directly linked to TMX accommodation measures, while others provide key supports for recommendations issued in the Canada Energy Regulator’s Reconsideration Report on the project.Footnote 6

As previously discussed, there was a high concentration of resources, engagement efforts, and pilot projects in the Pacific region. Financial tables developed by the lead department during the OPP’s planning phaseFootnote 7 indicate that close to a quarter of the OPP’s total funding was earmarked for the West Coast compared to 13% for the Atlantic and 14% for the Arctic regions (the remaining 48% were categorized as National investments). In terms of engagement and partnership activities, statistics pulled from TC’s OPP Stakeholder Engagement Solution (OPPSES) database suggested that over 85% of tracked events took place in the Pacific regionFootnote 8 (see Figure 6). Note that these figures do not reflect a full and accurate picture of all OPP engagement as A) OPPSES was only available to TC staff and B) there could have been greater uptake of the tool by West Coast program representatives.

Figure 6. Engagement events by region (OPPSES data)

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of engagement events tracked in OPPSES by region. There were 1276 events in the Pacific, 60 in the National Capital Region, 57 in the Atlantic, 33 in Ontario, 31 in Quebec, 24 in the Arctic, 3 in the Prairies and Northern Region, and 5 events that occurred across multiple regions.

While this element of the OPP’s design was clearly intentional, several interviewees felt that it created dissonance with the initiative’s branding as a comprehensive, national strategy to address marine safety and environmental issues, contributing to a sense of dissatisfaction among some Indigenous groups and stakeholders. Internal sources indicated that certain activities such as engagement were particularly under-resourced outside of the Pacific, placing strain on staff in other regions to do work off the side of their desks in order to meet partners’ needs and expectations. Some external interviewees expressed concerns that in targeting activities to allay public fears about tanker traffic and the transportation of oil (activities which they felt were already highly regulated), the OPP may have expended resources that would have been better spent tackling lower profile, but more impactful, safety and environmental issues (such as ageing sewer systems in coastal cities).

Finding 4: Internal services and Indigenous groups had limited opportunities to provide input into program planning and development, leading to underestimations of the time and resources required for some activities.

“There was a huge push to develop the program very rapidly, so initiatives were developed in a tight circle of people without a lot of broader engagement.”

The design of the OPP was also affected by the need for a quick turnaround and a centralized work environment during its development. Several internal interviewees (including staff who were involved during the planning phase) indicated that, due to the realities of policy development within the federal government, the OPP’s development was rushed and mostly completed in a top-down, internally focused fashion, with limited opportunities for enabling services or Indigenous groups to provide input. As a result, some miscalculations were made in the costing and timelines for key internal enabling functions, which led to challenges during the OPP’s early implementation. While the injection of human and financial resources was helpful to PDAs, the preceding era of cuts and austerity made it difficult for some internal processes like staffing, classification, and IM/IT to meet expectations and align with OPP projections. This observation was corroborated by DFO’s internal evaluation of the OPP’s first phase, which traced key challenges within data-heavy projects to insufficient consultation with IM/IT specialists and regional expertise during planning.Footnote 9 In some cases, mitigation strategies (such as the internal reallocation of funds) were implemented to address these challenges.

“One thing that we should have done differently was budgeted more time for building partnerships. We were naïve about that.”

Many interviewees also felt that the time, expertise, and resources needed for meaningful Indigenous inclusion had been misjudged. This contributed to a slower start than anticipated for initiatives that relied heavily on engagement with Indigenous groups, especially in cases where relations with the federal government and/or specific departments had been strained or non-existent in the past. A case study of the Proactive Vessel Management (PVM) sub-initiative flagged under-estimations of the time required to build collaborative relationships with Indigenous groups as a key challenge,Footnote 10 while survey respondents rated “insufficient time budgeted for building external relationships” as the factor that caused the most difficulties for the OPP’s implementation (with approximately 44% indicating that it had created challenges to a moderate or great extent). Within CCG, engagement functions were not funded with the grants and contributions required to support Indigenous participation, resulting in a need to reallocate resources and leading to uncertainty in budgets from year to year.

In addition to these resource and relationship shortfalls, PDAs were unaware of just how much capacity constraints within Indigenous groups would hinder their ability to participate in OPP activities. As later sections of this report will discuss, this issue was worsened by the push for multiple sub-initiatives to simultaneously establish new relations with Indigenous groups, a task that was not always well coordinated within or between PDAs.

3.3 Process and implementation

3.3A Federal collaboration

Finding 5: Strong federal collaboration was critical to the implementation of many OPP activities. While collaboration within PDAs was generally effective, horizontal dynamics were more challenging.

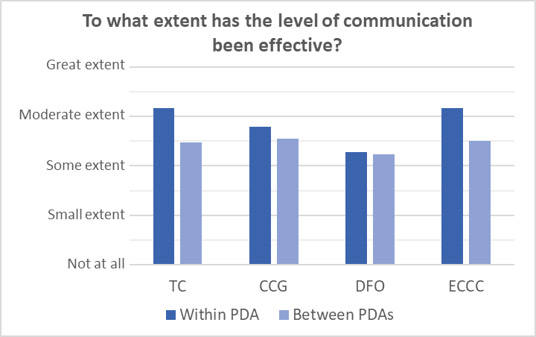

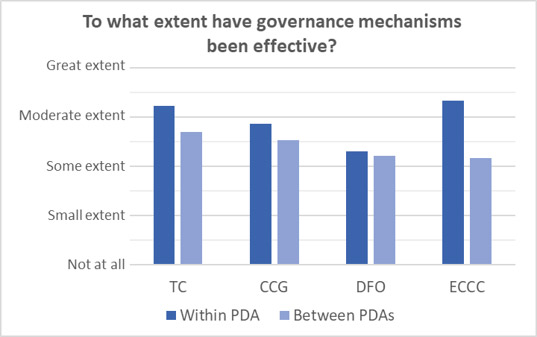

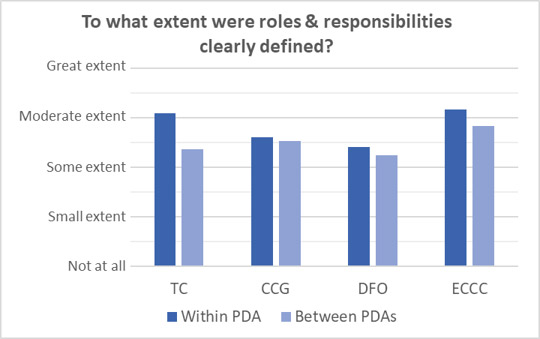

Effective collaboration within and between PDAs was critical to achieving many of the OPP’s intended outcomes. Over a quarter of its 57 sub-initiatives involved horizontal work, with many others requiring coordination across diverse departmental teams and branches. In general, evidence suggested that while collaboration within departments was fairly effective, horizontal dynamics presented greater challenges. As seen in Figure 7, horizontal collaboration was consistently rated as less effective than collaboration within PDAs by survey respondents. Similar ratings were found for specific elements of collaboration, including governance mechanisms, level of communication, and clearly defined roles and responsibilities (see Appendix F.1 for ratings). Lower ratings for elements of intradepartmental collaboration (particularly roles and responsibilities) were found among respondents from DFO and CCG, likely reflecting the fact that: A) OPP activities were spread widely throughout teams, branches, and regions within DFO-CCG, and B) both DFO and CCG maintain distinct organizational and governance structures, increasing the complexity of coordination. The OPP secretariat within this department/agency was also restructured and moved around several times over the course of the initiative, which may have disrupted oversight and collaboration functions.

Figure 7. Average federal collaboration ratings by PDA (internal survey data)

Note: NRCan data too limited for meaningful comparison

Text version

This bar chart shows average ratings given by internal survey respondents in each OPP partner department/agency (excluding NRCan) in response to the question "To what extent has collaboration been effective?" Ratings are presented separately for collaboration within PDA (i.e., intra-departmental) and collaboration between PDAs (i.e., horizontal). On a scale from 0 ("Not at all") to 4 ("Great extent"), TC respondents gave an average rating of 3.49 for intra-departmental collaboration and 2.63 for horizontal collaboration. CCG respondents gave an average rating of 3.13 for intra-departmental collaboration and 2.53 for horizontal collaboration. DFO respondents gave an average rating of 3.09 for intra-departmental collaboration and 2.48 for horizontal collaboration. ECCC respondents gave an average rating of 3.17 for intra-departmental collaboration and 2.17 for horizontal collaboration.

A key feature of the OPP was the strong horizontal governance structure put in place to ensure coordination and to oversee progress. Many internal interviewees saw the OPP’s governance mechanisms as helpful and effective, providing a strong basis for facilitating collaboration, collecting performance information, and resolving issues among PDAs. Several senior interviewees, in particular, felt that the dashboards and data collected departmentally and through horizontal governance structures met their expectations and were helpful for generating discussion, making decisions, and identifying project delays. However, the value of the horizontal governance and oversight was less clear to working level-staff, some of whom viewed the multiple layers of inter- and intra-departmental governance as cumbersome and struggled to manage the volume of administrative/reporting requirements on top of project delivery. The issue of reporting burden is discussed in detail in the Performance Information section.

Evidence from interviews and internal survey data also suggested that there were issues with communication within the OPP. Information did not always flow consistently between related initiatives, between headquarters and regional staff, or between senior management and the working-level. Multiple internal interviewees mentioned that it was hard to find out who was even leading a given project, and suggested that a centralized, updated record with names and contact information of team leads would have been helpful for OPP staff.

Roles and responsibilities at the horizontal level were also unclear at times, particularly between organizations with linked/complementary mandates. This led to some instances of confusion and/or duplication, including two examples which were documented through the 2021 OPP Case Studies:Footnote 11

- The TC-led EMSA platform (which was co-designed with Indigenous communities as a TMX accommodation measure) and the CCG-led Collaborative Situational Awareness Portal (CSAP) both aimed to increase collaboration with Indigenous groups and enhance communities’ awareness of local marine information. Although originally conceived as separate projects, over time it became clear that they were fulfilling very similar purposes. In 2021, TC and CCG decided to combine resources and move forward with EMSA as the official situational awareness platform.

- The Proactive Vessel Management (PVM) sub-initiative was intended to modernize the regulatory and oversight framework around marine traffic issues through collaborative dialogue forums and pilot projects such as the Haida Gwaii Voluntary Protection Zone.Footnote 12 The initial scope of the PVM was too broad, which created tension and confusion around the respective roles and responsibilities of TC and CCG. These issues were ultimately resolved as activities solidified.

Other horizontal challenges included disagreements about who should be leading certain activities (for example, engagement with Indigenous groups) and the sharing of data between PDAs and with external partners, which was hindered by both technological limitations and reluctance within some departments; on this topic, one internal interviewee noted that the push towards open data and transparency in government was still very much a work in progress.

“The five departments all have different mandates and responsibilities. It was complex. We were like five people trying to achieve the same thing, but in five different ways.”

While these issues were not universal, they were significant enough to prompt one external interviewee to observe that PDAs sometimes seemed to be in competition with each other, especially in the OPP’s early days. Overall, survey and interview respondents seemed to see these horizontal challenges as more systemic than interpersonal, reflecting cultural differences in departmental structures, priorities, and communication styles. In fact, roughly 52% of survey respondents indicated that “difficulties stemming from differing partner department mandates and cultures” created challenges for the OPP’s implementation to a moderate or great extent. This number was especially high among ECCC respondents (83%). Prior to OPP, close collaboration between PDAs had been limited and even difficult in some cases. This, coupled with the sheer size and variety of the initiative and the siloed nature of departments, made it especially hard for individual teams to see how the work they were doing connected to other departments’ activities and the achievement of OPP results.

Other factors that hampered federal collaboration included: A) disparities in the level of time and effort PDAs were able to dedicate to collaboration, reporting, and engagement mechanisms and B) frequent staff turnover. This last factor was especially important given that the success of many OPP activities hinged on strong working relationships, both internal and external. To this point, 40% of survey respondents indicated that “high levels of staff turnover” had created implementation challenges to a moderate or great extent; this number was even higher among CCG respondents (60%). While the rate of turnover was not something PDAs could directly control, the nature of OPP as a time-limited, B-base funded initiative may have prompted staff to view their time working within the OPP as a steppingstone or an avenue for an accelerated promotion before moving on to other things. In this view, having more stable, long-term funding from the outset could have helped staff to see that there was room to grow within the initiative, enhancing recruitment and retention.

“We need that integration within and across departments for all our big environmental questions. There is room for improvement, but it’s been a great success.”

Even with these difficulties, several interviewees (especially at the senior level) felt that navigating the challenges of horizontal work and pulling together over the course of the OPP ultimately led to strengthened relationships, better communication, and increased clarity of roles between PDAs. The skills and momentum developed from working together across departmental boundaries in the OPP were considered strong success factors that would serve PDAs well in the future. As one of the first large initiatives involving close collaboration between these departments, the OPP demonstrated that PDAs could work together as a federal family to pursue complex horizontal goals. Given the new ways of working that the OPP introduced, some amount of friction was inevitable and as one interviewee observed, probably healthy in the long term, in terms of facing and resolving difficult and enduring issues such as those encountered through the EMSA/CSAP and PVM sub-initiatives.

Finding 6: There were issues coordinating and tracking engagement and partnership activities in a consistent and reliable manner, which placed strain on Indigenous groups and stakeholders. Many improvements to the engagement process occurred as the OPP matured, but opportunities for improvement remain.

“You go out one day and meet with an Indigenous group only to find out that another department met with them the previous day. There was consultation fatigue that we could have mitigated.”

Issues with federal collaboration over the course of the OPP also affected progress with partners, particularly Indigenous communities. Many communities are chronically under-resourced to respond to pressures in their territories, and mobilizing the capacity needed to respond to federal requests for consultation and engagement (in terms of time, funding, personnel, and/or technical knowledge) while also managing critical health and environmental issues is an ongoing challenge.Footnote 13 Within the OPP, the magnitude and diversity of engagement and partnership activities represented a significant workload for Indigenous groups in terms of attending meetings, reviewing reports and technical documents, and fulfilling administrative requirements. Although there was a strong appetite to participate in OPP activities, multiple data sources suggested that shortfalls in coordination and losses of institutional memory due to turnover contributed to confusion, frustration, and fatigue among partners, with individual sub-initiatives often pursuing engagement efforts in isolation from each other. In fact, internal survey respondents rated “Coordinating engagement activities with other initiatives, departments, and agencies” as the least effective aspect of Indigenous inclusion within the OPP. This issue was further exacerbated by A) the COVID-19 pandemic, which created new demands on partners’ time and resources, and B) a general lack of understanding about the boundaries between similar and/or linked federal activities. The lack of PDA coordination was also a barrier for non-Indigenous groups, with some external interviewees describing their experience of engaging with multiple departments on the OPP as confusing or disorganized.

Evidence from internal and external sources suggested that PDAs could help to alleviate capacity strain and confusion by:

- Providing longer-term and more flexible sources of capacity funding,

- Streamlining application and reporting processes,

- Maintaining clear and regular communication with partners,

- Sharing reports and documentation in a timely fashion (with plenty of advance notice to review and provide comments), and

- Pursuing a more coordinated approach by enhancing the tracking and sharing of engagement records between sub-initiatives and aligning related engagement and partnership activities (e.g., implementing a single window approach).

To their credit, PDAs recognized many of these issues early on and made efforts to shift towards a more centralized/integrated engagement approach. For example, CCG established Indigenous Relations and Partnership (IRP) units in each region to act as a single window into the department’s OPP activities,Footnote 14 while TC created a new, longer-term source of capacity funding through the Indigenous and Local Communities Engagement and Partnership Program to supplement short-term support available through the existing Community Participation Funding Program.Footnote 15 The lead department also implemented a National Integration Model (NIM) for engagement activities, where separate regional engagement teams with representation from all PDAs were connected through a central national hub and interacted via bi-weekly conference calls and (pre-COVID) in-person workshops.Footnote 16 The NIM was well received internally and considered a valuable avenue for sharing high-level information and lessons learned. However, uptake of this and other coordination mechanisms was inconsistent, and many engagement activities continued to take place in a siloed fashion (at least from the perspective of Indigenous groups and stakeholders). While individual PDA engagement statistics were regularly collected and fed into a central roll-up function at TC for reporting purposes, there was initially no formal mechanism for tracking and sharing detailed engagement data across PDAs, resulting in limited awareness of other departments’ interactions with partners. The OPPSES database, which was originally intended to address this gap, is still a TC-only tool.

3.3B Evolving approaches and other implementation factors

Finding 7: OPP staff were agile and effective in responding to significant changes over the course of OPP implementation, reflecting the program’s spirit of flexibility and experimentation.

“The mindset of a lot of the people working in OPP was very open to trying things out. There were a lot of amazing people who could test what was possible in government.”

Given the challenges associated with horizontal collaboration, a strong success factor for the OPP was the agility and competence of its working-level staff. A key theme emerging from the OPP Case Studies was that many sub-initiatives (such as EMSA, PVM, and the Building Meaningful Partnerships sub-initiative (BMP)) had encountered unexpected challenges which had pushed them to evolve from their original design.Footnote 17 In general, OPP staff were responsive and flexible in managing these changes, and both senior management and external interviewees were impressed with their ability to move projects forward under challenging conditions such as the COVID-19 pandemic, impractical timelines, and the complexities of engagement/partnership processes. One external interviewee observed that the OPP demonstrated a level of flexibility and openness that had not existed before in the federal government, with staff actively listening and adapting their approaches in response to partners’ input. Some examples of this ability to adapt included:

- The creation of the Local Communities Engagement and Partnership Program to supplement existing funding structures and support Indigenous capacity when it became clear that communities were struggling to participate in key activities,

- Engagement staff shifting to presenting at existing industry sector or community meetings rather than organizing new forums and meetings for groups to attend,

- Reallocating extra resources within the OPP envelope to bolster underfunded activities/areas, and

- Rapidly pivoting to remote operations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These examples speak to the overall spirit of experimentation and willingness to take on risk that characterized the OPP, which seems to have served the initiative well. The license to experiment and explore new approaches also allowed PDAs to explore new co-development and joint governance structures with Indigenous partners, which is discussed in detail in the Indigenous Inclusion section.

Survey and interview respondents identified several other factors that impacted the OPP’s implementation. Unsurprisingly, the pandemic was rated as the biggest challenge to the OPP’s implementation, with 51% of respondents indicating that “delays related to COVID-19” had created a moderate or great degree of difficulty by limiting in-person training and engagement activities (which was often preferred over virtual formats by Indigenous groups), slowing down legislative/policy processes, and delaying construction and field work projects. Sub-initiatives operating in remote and Northern areas were especially hard hit due to existing infrastructure and connectivity issues. Although the COVID-19 pandemic hindered progress overall, a minority of internal respondents pointed out that it also provided opportunities for focused, uninterrupted work and prompted innovative engagement strategies and uses of technology that would probably continue to benefit PDAs in the future. For example, normalizing remote work could potentially expand limited hiring pools for highly specialized and technical positions.

While the pandemic was obviously beyond the control of PDAs, many other hindering factors, such as the underestimation of the human and financial resources needed for enabling functions and the insufficient time budgeted for building external relationships, were linked to issues during the OPP’s planning and design phase. For a full list of hindering and facilitating factors that impacted the OPP’s implementation, see Appendix F.2.

3.4 Progress and results

Finding 8: Despite the challenges associated with the early implementation and pandemic-related delays, the OPP had significant positive impacts and made tangible progress in key thematic areas.

Analysis of dashboards and results templates suggested that just over half of the OPP’s 57 sub-initiatives had met their targets or were expected to do so within planned timelines (see Appendix F.3 for details). These figures aligned with interview data, which reflected a roughly even split between internal interviewees who suggested that targets for their sub-initiative had been met or exceeded and those who flagged a need for more time or resources to deliver on key commitments. According to interviewees and internal documentation, these delays largely reflected the unexpected complexities of engagement and partnership activities as well as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

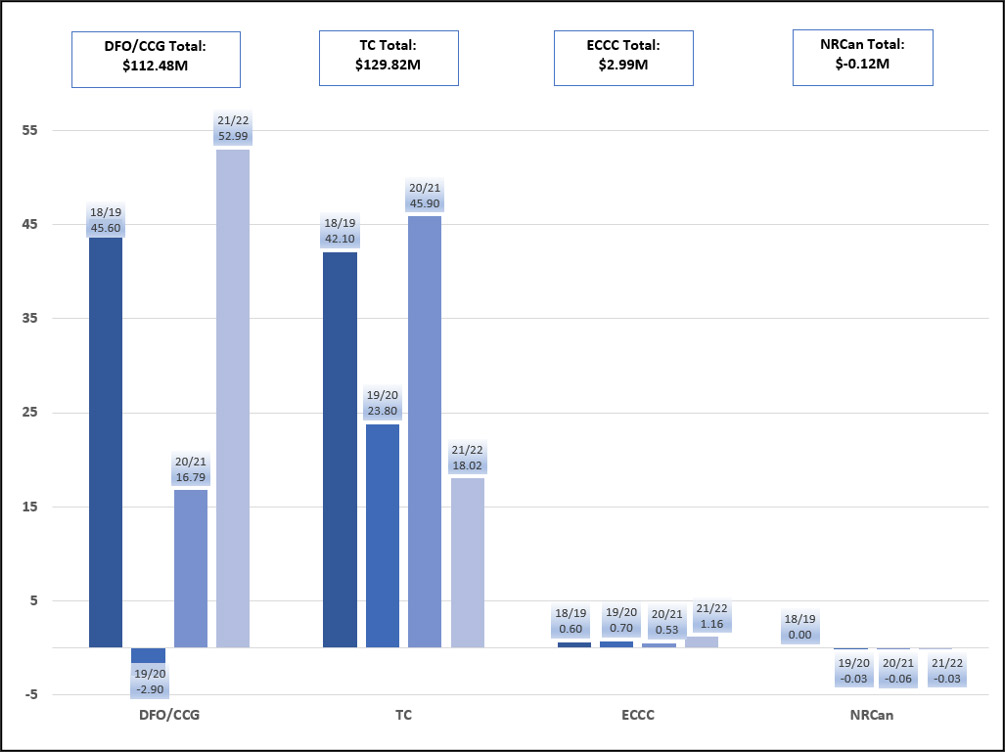

As discussed, the pandemic impeded the procurement and delivery of goods and services, delayed the achievement of certain milestones, and disrupted the overall implementation of the OPP – particularly for projects that were highly dependent on fieldwork, training, construction, and collaboration with Indigenous groups and stakeholders. The pace of some sub-initiatives was further slowed due to underestimations of the time and resources needed to support internal enabling services as well as conducting meaningful Indigenous engagement. Financial analyses indicated that these delays had a significant impact on the scheduled disbursement of funds within the OPP, resulting in large yearly amounts that needed to be either A) reprofiled to future years, B) reallocated within the OPP envelope, or C) re-directed to similar marine programming needs. From the 2018/2019 to 2021/2022 fiscal year (FY), the OPP spent $1.12B of its $1.51B budget (84%) as planned.Footnote 18 Detailed financial figures can be found in Appendix F.4.

Analyses of internal financial tables indicated that reprofiled/reallocated/redirected amounts within the OPP consisted largely of Contribution and Capital funding, particularly at DFO-CCG and TC. Projects that reported residual funding amounts of $10M or more in these categories were flagged for further analysis.Footnote 19 Out of 9 projects (6 at DFO-CCG, 3 at TC) that fit these criteria, 100% had been classified as needing an extension to complete their deliverables due to impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, Northern considerations, and/or prolonged negotiations with Indigenous groups. For example, educational institutions receiving funding through the TC-led Marine Training Program were unable to provide placements and hands-on training to students during the height of the pandemic, while a project to install new CCG search and rescue stations was delayed for a variety of reasons, including ongoing negotiations with Indigenous communities and the impact of the pandemic on procurement and construction schedules. To address the fallout from these kinds of disruptions and mitigate the negative impacts on external partners, some PDAs reprofiled existing funding to 2022-23 with a view to completing the delivery of OPP activities within this revised timeframe.

PDAs were active in monitoring and reviewing OPP funding, allowing them to manage resources in an agile/flexible manner. In addition to reprofiling funds to future years within individual projects, this approach allowed them to reallocate funds to bolster other OPP sub-initiatives if necessary and/or to redirect funds to respond to similar marine programming needs. Within TC, funding amounts that were not carried forward or reallocated were managed by Corporate Finance and redirected towards related marine priorities such as the Whales Initiative, the Marine Safety and Security Program, and the National Aerial Surveillance Program. Within DFO-CCG, the OPP Secretariat and Chief Financial Officer’s team collaborated to provide financial oversight for each project, which was reviewed and analyzed on a regular basis; any residual yearly amounts resulting from individual projects were either reprofiled to future years or reallocated within the OPP envelope.

Figure 8. Average progress ratings by PDA (internal survey data)

Note: NRCan data too limited for meaningful comparison

Text version

This bar chart shows average ratings given by internal survey respondents in each OPP partner department/agency (excluding NRCan) in response to the question "To what extent is the OPP on track to achieve intended results?" On a scale from 0 ("Not at all") to 4 ("Great extent"), TC respondents gave an average rating of 3.07, CCG respondents gave an average rating of 3.05, DFO respondents gave an average rating of 3.39, and ECCC gave an average rating of 3.

Despite the significant setbacks associated with the pandemic and other factors, PDAs had generally favourable views of the OPP’s overall progress (see Figure 8). Approximately 71% of survey respondents indicated that the OPP was on track to achieve its intended results to a moderate or great extent, while many internal interviewees shared examples of success stories that illustrated the OPP’s positive impacts in the marine sector, including:

- The co-creation of the EMSA platform: Described by some participants as “reconciliation in action”, the early and ongoing inclusion of partner communities was central to the platform’s success.

- The impact of grants and contributions among partners: Transfer payments through programs like the Coastal Restoration Fund (CRF) allowed NGOs and other partners to collect critical data and rehabilitate aquatic habitats across 8 provinces and territories.

- Enhanced community relations and response capacity through training and infrastructure investments: The Indigenous Community Boat Volunteer, Community Response Training, and CCG Auxiliary programs were effective in bolstering relationships between CCG and participating Indigenous communities.

- Increased monitoring presence in the Arctic: OPP funding empowered Inuit stewardship of Arctic coastlines and even led to an Inuit spotter identifying a pleasure craft contravening COVID-19 restrictions in the Northwest Passage,Footnote 20 providing a strong example of successful federal-Indigenous collaboration.

The document review and interview responses also highlighted many concrete outputs that contributed positively towards increasing the safety of marine shipping, improving emergency response, protecting marine species and ecosystems, advancing collaboration with Indigenous groups, strengthening the marine evidence base, and bolstering public awareness:

- 33 marine charts completed to improve navigation in key ports,

- over 16,000 KM of coastal imagery collected,

- 5 new state-of-the-art weather buoys deployed,

- 8 pieces of legislation created or revamped to strengthen safety and environmental protections

- 500+ abandoned vessels addressed,

- over 1,900 engagement activities conducted with Indigenous groups,

- signing the first Reconciliation Framework Agreement for Bioregional Oceans Management and Protection,

- 50+ papers, reports, and other materials published on oil spill science,

- 3 POR studies conducted to assess public impressions of marine safety,

- and more (see Appendix F.3)

As seen in Figure 9, of the 336 individual projects announced and tracked through the OPP’s public website,Footnote 21 nearly half fell under Pillar 2 (Preservation and restoration of marine ecosystems). The fewest number of projects were linked to Pillar 3 (Indigenous partnerships); however, many projects under Pillars 1, 2, and 3 involved PDAs partnering with Indigenous groups. Unsurprisingly, OPP activities were mostly focused in coastal areas and the highest concentration of projects was located in the Pacific region, as seen in Figure 10.

Figure 9. OPP projects by pillar

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of projects by OPP Pillar. Thirty-two percent of projects fell under Pillar 1: State-of-the-art marine safety & prevention, 47% fell under Pillar 2: Preservation & restoration of marine ecosystems, 3% fell under Pillar 3: Indigenous partnerships, and 18% fell under Pillar 4: Stronger evidence base, increased community participation & public awareness.

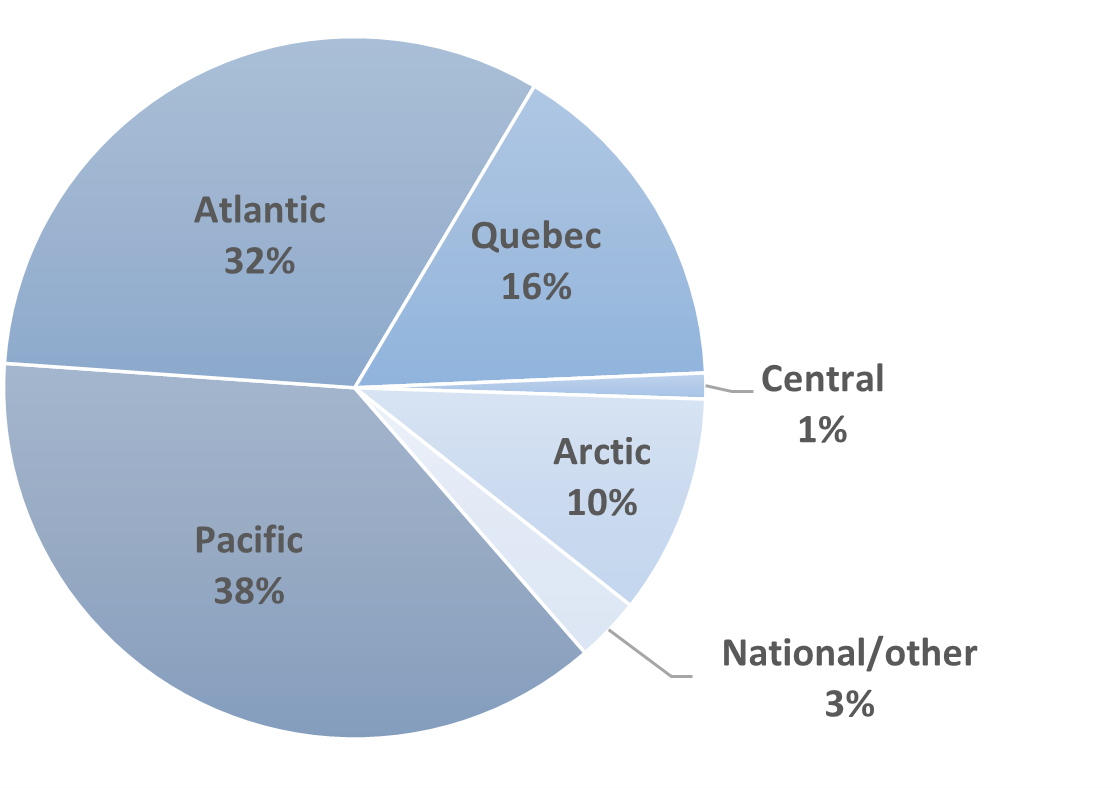

Figure 10. OPP projects by region

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of OPP projects by region. Thirty-eight percent of projects were in the Pacific, 32% were in the Atlantic, 16% were in Quebec, 10% were in the Arctic, 1% were in the Central region, and 3% were either National or other.

Assessing the achievement of results at the strategic level was more challenging. During the Treasury Board submission phase, PDAs developed six targets linked to key initiatives to track progress towards the OPP’s overall strategic outcome (“A world-leading marine safety system for Canada’s three coasts that protects marine ecosystems”). Three of these targets were met or exceeded:

- Target: 90% of projects funded through Coastal Restoration Fund (CRF) contribution agreements lead to rehabilitation of aquatic habitats

- Result: 100% of CRF-funded projects restored important coastal aquatic habitats, with over 60 projects worth over $70 million funded to date.

- Target: By 2022, a reduction in the number of abandoned, derelict and wrecked vessels present in Canadian waters

- Result: At the time of writing, 545 vessels of concern were addressed, surpassing the planned target of 275.

- Target: By 2022, 100% of policies and operational response plans are supported by scientific, local/traditional, and other relevant information/knowledge

- Result: While progress in this area is harder to quantify, several OPP activities such as gathering input from Indigenous groups and stakeholders, conducting oil spill research, and collecting coastal data suggest that this target has been met (with some aspects being continuous/ongoing).

Work on the fourth target encountered delays, but was on track to meet adjusted timelines:

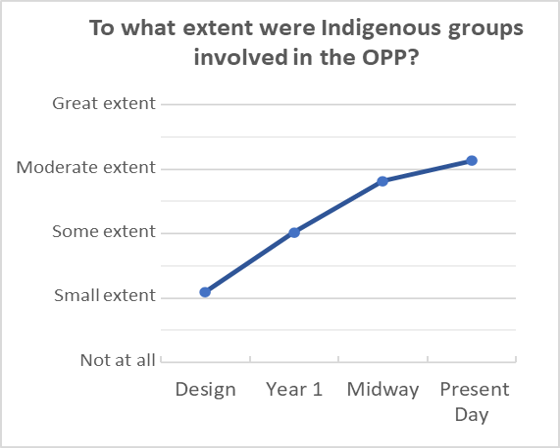

- Target: By 2027, an increased number of interested Indigenous groups are active partners in Canada’s marine safety system